The Mansion at the Muckenthaler Cultural Center Celebrates Its 100th Anniversary

- Joel Beers

- Oct 6, 2025

- 9 min read

In its centennial year, the Fullerton mansion connects 21st-century arts and culture to Orange County’s early history.

For 100 years, the Muckenthaler Mansion and its surrounding grounds have stood as both a dream fulfilled and a gift passed on. The dream belonged to Walter Muckenthaler, the son of German immigrants turned prosperous citrus rancher, who commissioned and helped design the stately 18-room property and surrounding grounds on 8.5 rolling acres in west Fullerton.

The gift came from his son, Harold, who in 1965 handed the estate to the city with one condition: it be devoted to the arts. Six decades later, the Muckenthaler Cultural Center still delivers – offering some 100 events a year, ranging from theater and visual art to car shows, concerts, lectures, and children’s and adult arts education.

At least, that’s the familiar story. But there are some usually overlooked details that complicate it. For instance, it was Adella, Walter’s wife, who first floated the idea of donating the property – at a Chamber of Commerce Fine Arts Commission meeting in 1964. And, less than a year before that, her son Harold (Walter had passed in 1958) tried to rezone the estate for apartments, then condominiums – plans shot down after 150 neighbors petitioned against it, fearing increased density would put their children at risk.

Most surprising to Callie Johnson, co-founder of the center's resident theater company, the Electric Company Theatre and – whose new play marks the mansion’s centennial this weekend – are two other facts:

It wasn’t ranching but oil money that financed the mansion.

That oil wealth came from Adella, daughter of Placentia pioneer Samuel Kraemer and a descendant of famed landholder Bernardo Yorba.

“Not that Adella needs defending, but her prominence in all this is not mentioned nearly as much as Walter’s or Harold’s,” said Prendiville Johnson, who also serves as communications director for the Muckenthaler. “Her contribution – both in the initial wealth of the young couple and in turning (The Muck) over to the city – has been largely eclipsed.”

None of this erases the Muckenthalers’ generosity or its civic footprint. (Walter spent eight years on Fullerton’s city council, overseeing construction of its first city hall, now the police station, and nine years on its planning commission). But when seen whole, the story is larger than one self-made man’s triumph. It’s a layered saga spanning three families – two immigrant German, one Californio ranchero – whose histories converged through oil, agriculture, marriage and land; familial lines that had enormous impact on the development of Placentia, Yorba Linda and Anaheim, and in a cultural legacy that still crowns a Fullerton hill a century later.

SIDEBAR: ‘The Centennial Project’

The second of new original plays created for the Muckenthaler Mansion’s 100th anniversary opens this weekend. Unlike the spring production, staged outdoors and designed to give elementary students a sense of Fullerton life 100 years ago, “The Centennial Project” brings audiences inside the historic mansion for an immersive, choose-your-own-adventure experience.

“It is an experience,” says playwright Callie Prendiville Johnson, co-founder of Electric Company Theatre, the Muckenthaler Cultural Center’s resident company. (She’s also communications director for The Muck.)

It features 27 actors grouped into two tracks, each running in three 10-minute cycles simultaneously. The first follows contemporaries of the Muckenthaler family, including family members, city movers, mansion architect Frank Benchley and Fullerton silent film star Sharon Lynn. The second blends fact and fiction and chronicles a bootlegging operation in the city.

Actors move throughout the mansion, and each audience member chooses which character to follow or which room to enter.

“All of these characters are living their own story, but you might not catch everything the way you would in a traditional play,” Johnson says. “You might see Walter (Muckenthlaer) in one room, then follow the maid into the next and witness a different interaction. Audiences have agency as to what character to follow or room to enter. It’s more like a walking adventure than a plot-driven play.”

With multiple storylines and the logistics of actors moving from room to room and audience members following them, producing immersive theater is far more complex than a traditional play. But both Johnson and her husband Brian, the other co-founder of the company, are familiar with the form as spectators and producers. They watched the groundbreaking troupe Punchdrunk in New York several times and produced an immersive piece in Fullerton in 2016, which may have helped pave the way for their residency at the Muck.

“When we first approached CEO Farrell Hirsch in 2021, he knew of our previous immersive piece,” Johnson recalls. “He said, ‘In about five years the centennial is coming up, and we’ve been looking for someone to create something specific for that occasion.’ So we’ve been planning this for almost five years.”

Creating the piece required extensive research, with help from the Fullerton Library’s Local History Room. Prendiville Johnson compresses time – “I highly doubt all these people were in that mansion at the same time” – but she wanted to give authenticity to how the characters lived and planned their lives. However, one theme, relating to Adella and Walter Muckenthaler, is dramatic conjecture.

“Both came from large Catholic families but had only one son,” Johnson explains. “I’ve been talking with the actress playing Adella. These were the richest people in town, but even though it’s not on the (historical) record, having only one child could have been a source of disappointment, if not heartbreak.”

The immersive format blurs the fourth wall and heightens intimacy, helping audiences see these characters not as dusty relics from the past, but as real human beings, Prendiville Johnson says.

“People are people, no matter the time period. And by making this so intimate, with patrons inches away and watching someone live their life rather than sitting on the other side of a proscenium and hearing them talk about it, you get a much more intimate view of that person’s life.”

When: 7 p.m. Oct. 14-Nov. 5. Tuesdays and Wednesdays, also Thursday, Oct. 30

Where: Muckenthaler Cultural Center, 1201 Malvern Ave., Fullerton

Cost: $49.02

Contact: electriccompanytheatre.org

The Muckenthaler line

This family’s American story begins with Martin and Elizabeth Muggenthaler, who sailed from Antwerp, Belgium in 1854. Somewhere on the voyage, their name was misspelled, and when they landed in America 52 days later, they kept it. They were part of a massive wave of German immigrants; in 1854 alone, more than 215,000 Germans arrived, the second-highest total after 1884. They settled in Minnesota, where their son Albert was born in 1862, and later moved to a 400-acre farm in Paxico, Kansas.

In 1881, Albert visited Anaheim, working in construction and vineyards there – then a German colony with a strong Spanish-speaking presence – before returning to Kansas. He married in 1888; Walter was born in 1896. Something about California lingered, though. Twenty-eight years after visiting Anaheim, at age 47, Albert uprooted his family of eight children and headed west.

He bought 10 acres in Anaheim from the Dominican Sisters at St. Catherine’s, built a home and raised potatoes along with a small Valencia orange grove. The family also managed a dairy and two bakeries. Walter attended Anaheim High, acted in a few plays and then helped with the bakery.

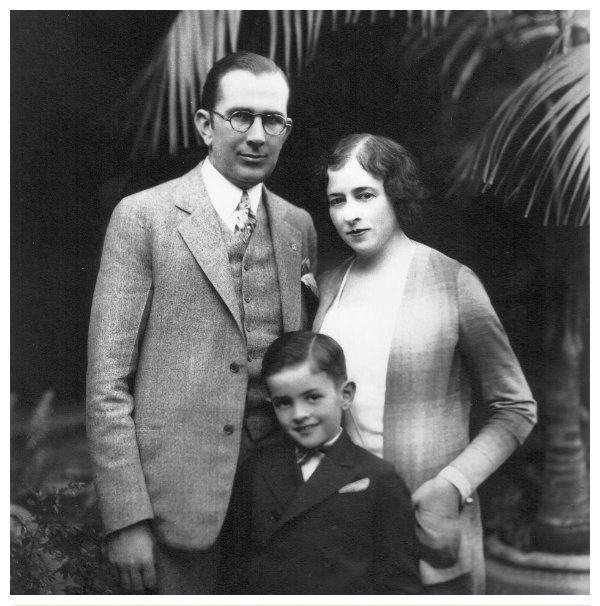

A couple of years after graduation, in 1915, he had saved enough to enroll in UC Berkeley’s architecture and design school. Money troubles and World War I cut his education short. Discharged from the Navy for a heart murmur, he worked as an engineer for the Santa Fe Railroad – and found love at St. Boniface Catholic Church with Adella Kraemer.

The Kraemer Line

Adella’s genealogy on her father’s side parallels that of Walter’s. Her grandfather, Daniel Kraemer, emigrated from Germany in the 1850s with money to invest. On his first California visit, he bought 4,900 acres in what is now Placentia for $4.04 an acre, later moving his family – including Samuel, Adella’s father – to the ranch. Daniel would become one of Placentia’s founders.

In 1886, Samuel Kraemer married Angelina Yorba, great-granddaughter of Bernardo Yorba. The couple had six children; Adella was their first. Like Walter, Adella was a devout Catholic. As the eldest daughter, she often served as a second mother to her siblings. In 1918, she married Walter at St. Boniface. Their honeymoon at Riverside’s Mission Inn – with its lush courtyards and fountains – likely inspired the landscaping that would soon adorn their Fullerton estate.

Today, the Muckenthaler grounds serve as an arts and culture center for the city of Fullerton. PHOTO 1: Frank Benchley, the architect of the two-story, 18-room Muckenthaler Mansion, also was the vision behind several other Fullerton landmarks, including the California Hotel (now Villa del Sol), the former Masonic Temple at the corner of Chapman Avenue and Harbor Boulevard, and a well-preserved bungalow on Pomona Avenue. PHOTOS 2 & 3: The mansion's solarium, located in its southeast corner just right of the main entry, is an octagonal structure with Palladian windows. It has been used for many purposes over the last 100 years, including housing exotic plants favored by Walter Muckenthaler, a team room and a bar area for wedding and corporate events. PHOTO 4: A stone gazebo, located a few steps from the mansion's front door, once sat beside a reservoir that was part of the property's citrus grove irrigation system. It is sometimes used today as a photo spot for weddings. PHOTO 5: Arts programming for children, both on-site and off-site, has been a staple of the Muckenthaler Cultural Center since its inception. PHOTO 6: Sculpture gardens, which began to be added on the grounds, include eight 19th and 20th Century men's house posts from Papua, New Guinea. They are on long-term loan from the Bowers Museum in Santa Ana. PHOTO 7: The Muckenthaler's outdoor amphitheater opened in 1993 and greatly expanded the cultural center's programming options. Photo 3 courtesy of the Launer Local History Room at the Fullerton Library. All other Photos by Joel Beers, Culture OC

The Mansion

Oil was struck on Samuel Kraemer’s land in 1919, the same year that Adella and Walter married. With money now flush, Walter, then working as a surveyor for the city of Fullerton, could begin creating a dream home that would include the couple’s first – and only – child, born in 1922. Construction began in 1923 and wrapped in 1925. Mediterranean Revival, the same kind on display at the 1915 San Diego Panama-California Exposition, was the style of the moment, and Walter and Adella leaned into it: red clay tiles, wrought-iron balconies, arched doorways, furniture, an ornate winding staircase imported from Italy, and gleaming-white stucco walls glowing in the late-day sun. At a reported cost of $35,000 (some $535,000 adjusted for 2025 inflation), the 18-room mansion was designed to impress – formal dining room, paneled library, a solarium, grand living spaces and sweeping upstairs quarters.

Surrounding it, terraces and balconies overlooked lemon, avocado and walnut groves, while interior courtyards blurred indoors and out. Gardens wound around fountains, footpaths, rolling lawns and gardens, an indoor atrium and a gazebo.

The Muckenthalers had only one child, but the mansion bustled with visiting ranchers, priests, civic leaders and, of course, lots of cousins and other family members. It quickly became part of Fullerton’s identity: proof that the little farm town had cosmopolitan aspirations.

By the time the property was deeded to the city in 1965, the orchards, which once covered 80 acres reaching to Commonwealth Avenue, had given way to subdivisions. Yet the house seemed built for its next act. Theatrical in scale, rich in history, it was ready-made for a cultural center. Today the Muckenthaler mansion remains the jewel of the property – galleries, classroom and performance spaces in and around a house that still dazzles.

It’s been part of the city’s story for 100 years, but its genetic roots stretch even further, before its construction and before mid-19th-century immigration, about as far back as roots can reach for any non-Indigenous person in Orange County.

The Muckenthaler Mansion was built atop a rolling hill just west of the intersection of present-day Malvern and Euclid avenues in west Fullerton. PHOTO 1: It overlooked 80 acres of citrus, avocado and walnut groves that stretched south to Commonwealth Avenue. Photo courtesy of the Launer Local History Room at the Fullerton Library. PHOTO 2: Overlooking the city it serves, the mansion is the centerpiece of a cultural center after it was donated to the city in 1965. Photo by Joel Beers, Culture OC

The Yorba Line

Adella’s maternal great-great-grandfather, Bernardo Antonio Yorba, was one of 19th-century California’s most powerful landowners. The son of José Antonio Yorba, a (possible) soldier with the 1769 Portolá expedition, Bernardo inherited Rancho Cañón de Santa Ana and added more land that encompassed holdings stretching across modern Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties.

A devout Catholic, Bernardo founded the Yorba Cemetery in 1834, today the oldest private cemetery in Orange County. But like many Californios, his empire shrank after U.S. annexation. Land grants bled away through lawsuits and taxes. Still, the Yorba name carried prestige well into the 20th century.

Through Adella’s mother, Angelina Yorba, that lineage flowed into the Muckenthaler household. So looked at broadly, the mansion Walter and Adella built wasn’t just an oil-and-citrus success story. It embodied – and continues to represent – a bridge between the ranchero past of Southern California and its suburban, postwar future.